Originally Published in the Adelaide Literary Magazine Awards Anthology, 2018

Somewhere in San Diego, California

If the woods are haunted, but the forest merely enchanted by shadows and soft light, into which realm does the stone staircase lead? And who will follow?

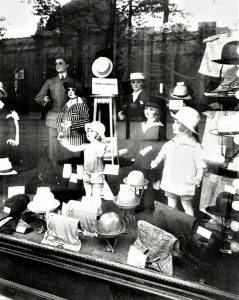

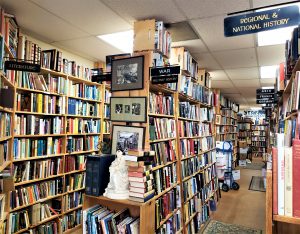

In a different era, as industrial wealth of the twentieth century flowered into great family fortunes, workmen were transported to a distant location and ordered to arrange a pile of rocks. It was an interesting task. Their employers—the founding fathers of our city—were determined to build a grotto in what was then wildland, something of a monument to affluence and ambition, a hint of things to come. Although, at first glance, it seemed like nothing more than a curiosity, the project had obviously been calculated, its site chosen with something in mind; the location was a place set apart from prying eyes and gentility, a place where the activities of a grotto could go unchallenged and remain hidden—never to be seen in newspapers or history books. Even now, long after the age of discretion and propriety has faded, the grotto remains a significant destination. Although suspicion has given way to appreciation over the years, something of the original aura persists; the structure still engages travelers as they explore pathways and wander in the shallow woods.

Every aspect was designed with care. Gray and orange rocks form not only a fount but also a series of walls and a staircase, steps that gently descend into an entanglement of oaks.

In the late afternoon, a larger vision becomes clear; odd angles reveal how the builders were able to use light, as it passed through tree branches and thick brush, to create an interesting experience; a journey of the mind no less than that of the body. Although the forest of our era has thinned considerably, the experience of traveling through light and shadow remains tangible.

Into the Grotto

Standing at the base of the stairs, one is immediately confronted with a choice; either climb back to the full embrace of sunlight or give way to momentum and continue the descent. Enjoy a reprieve from uncertainty or delight in a new adventure, the choice is yours. In the present era, the impact is less than what it must have been during the early twentieth century, back when the rocks were first arranged. And yet, the shadows cast by the staircase are still compelling, emphatic in a way that the escalators of a shopping mall, or even the steps of a venerable bank building, simply are not. The choice offered by the grotto is not only unavoidable—in that the traveler must either ascend or descend—it’s also something of a coy challenge. Are you willing to follow the shadows of an old stone structure? A few interruptions of darkness await you, but they will quickly give way to sunlight and the predictable elements of home. You can climb safely out of the forest and be on your way. Or would you prefer a deeper venture into the woods? Decades ago, when settlers were uncertain about their new surroundings, the experience must have been powerful.

Sadly, times have indeed changed. In the presence of traffic, and in the company of dogwalkers and children at play, the haunting ambience of the grotto is greatly reduced, perhaps returning only at night. However, at the moment of decision—when one must travel either up or down—a quick rush of anticipation is easy to feel, a reminder of the previous century, when the land was far more mysterious.

Even now, the mood of the place is difficult to capture and define. It’s as if the grotto is always becoming something different, reasserting itself in the face of history, crumbling slowly but nonetheless remaining defiant and vaguely disturbing.

As daylight fades, and hints of dusk become more insistent, the atmosphere truly changes. At the base of the stairs, sunlight begins to look a bit less capable of rescuing travelers from darkness. And the climb to the top begins to look forbidding. As night approaches, enchantment seems less likely than outright haunting, adventure being more a matter of survival than the experience of enjoyment. Again, from the vantagepoint of the stairs, these sensations become magnified, as the mind prefigures the body’s journey. Moreover, the mood of the place serves as a reminder; life is full of choices, many of which are difficult. At some point, before the full arrival of darkness, certain decisions must be made.

As for the question of who will follow the stairs as they beckon, either for an ascent to the world above—or a downward movement into the woods—a quick glance in any direction provides an answer.

The Visitors of Night

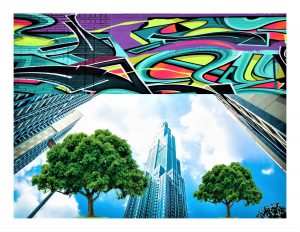

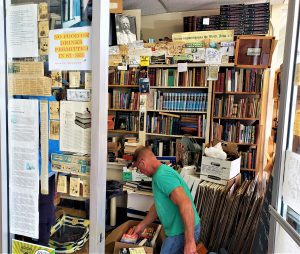

Empty whiskey bottles and beer cans, graffiti and the annoying presence of food wrappers have all converged on the old grotto, as if to challenge its claim to a mysterious past. The question of who follows its path is easily answered. At such moments, introspection can quickly transform into a feeling of grief. On one occasion, however, I was offered something more.

As I began my ascent, and tried to clear my mind of the inviting yet disquieting spirits of the place, I realized that I was not alone. It was a strange moment. I paused very close to a patch of graffiti—glaring red streaks of paint that reduced the grotto to a mere neglected ruin—as two people approached me. They were teenagers, a loud, enthusiastic boy and girl making their way through the afternoon. Both were laughing and sipping from plastic cups, the boy playing music on his phone, the girl texting on hers. They were moving with the ease of childhood, perhaps smiling at the rapid approach of their adult responsibilities. I smiled in return. We passed each other in the awkward manner of travelers who meet while going in opposite directions; they were heading to the base of the stairs I had just left. As they reached it, I glanced down and met the boy’s gaze. It was the familiar expression teenagers give to adults who are neither their parents nor teachers, but authority figures nonetheless, still capable of chastising them for their intimacy or demanding that they turn down their music. I did no such thing. My attention was elsewhere.

Although the day had been bright and warm, the air had recently begun to chill, and shadows had grown among the oaks, engulfing spaces that seemed to welcome the arrival of night—a sudden change in the mood of things. I wondered if they had noticed.